Peers, parents, and self-perceptions:

The gender gap in mathematics self-assessment

– by Anna Adamecz

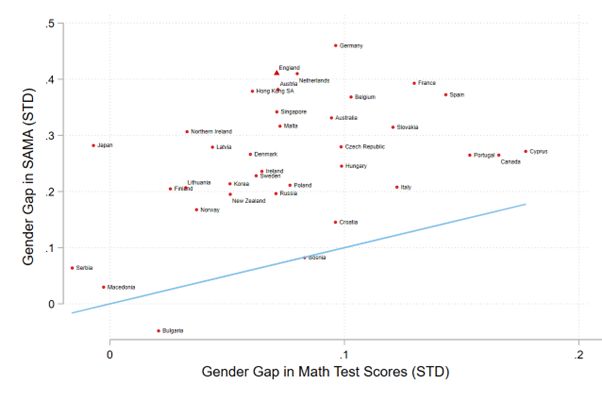

Across many countries, contexts, and fields, men tend to be more confident in their abilities than women. This is particularly true in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM). While the gender gap in math performance is small and narrowing globally, the gap in math self-assessment—how good individuals believe they are at math—remains large (see Figure 1). Boys overestimate their math skills, while girls tend to underestimate theirs, even when their abilities are the same. This confidence gap matters because it discourages girls from pursuing careers in math-intensive fields, contributing to the underrepresentation of women in STEM and reinforcing the gender wage gap. Addressing this issue could help ensure a more diverse and well-equipped workforce in professions like engineering, where demand remains high.

Figure 1: The relationship between the gender gap in math self-assessment (SAMA) and math test scores in the TIMMS data among Grade 4 pupils. The blue line represents equality, i.e. when the gender gap in self-assessment and test scores is the same. Source: Adamecz, Jerrim, Pingault and Shure (2025)

In this research, we investigated the drivers of the gender gap in math self-assessment. Using data from a UK-based twin study (the Twins Early Development Study, TEDS), we explore whether this gap is influenced by factors such as peer effects, parental biases, and societal stereotypes. Our findings confirm that objective math abilities explain only a small part of the gap, and that this gender difference is even more pronounced among boy-girl twin pairs. This suggests that children’s self-perceptions are shaped by more than just their actual math performance.

One key factor behind this gap is the influence of parents. We find that parents tend to overestimate boys’ math abilities and underestimate girls’, reinforcing gender stereotypes from an early age. This bias contributes significantly to the gap in how boys and girls assess themselves. Teachers also exhibit a similar, though smaller, bias in their assessments. These findings highlight how adult expectations can shape children’s perceptions of their own abilities, potentially discouraging girls from pursuing math-intensive fields. Our results suggest that interventions to close the gender gap in math self-assessment should also target parents and teachers, encouraging them to adopt more balanced assessments of children’s abilities.

We also examine the role of peer influences, particularly wihtin twin pairs. We find that boys benefit from having a confident male co-twin, as their self-assessment in math is positively correlated with their brother’s confidence. However, the same does not hold for girls: if a girl has a highly confident male twin, her own self-assessment in math tends to be lower. This suggests that girls may react differently to confident male peers, possibly feeling discouraged or overshadowed rather than motivated. While our results are not causal, they might offer a potential explanation for the gender gap in labor market outcomes, especially in top jobs and high-level managerial positions. For women, exposure to highly confident men might be more off-putting than for men. As top job positions are traditionally filled by confident men, women might suffer a double penalty: not only are they less confident than men, but their confidence is not supported in those environments (while men’s confidence might be). This phenomenon may serve as a barrier to both entry and progression for women in top jobs.

Anna Adamecz, John Jerrim, Jean-Baptiste Pingault, Dominique Shure: Peers, parents, and self-perceptions: the gender gap in mathematics self-assessment. Journal of Population Economics 2025. doi: 10.1007/s00148-025-01087-2.

This research was supported by the Economic and Social Research Council [grant number ES/T013850/1].