How value chains can support sustainable development

in Europe’s mountain regions

By Kirsty Blackstock and Gusztáv Nemes

Mountain regions in Europe are often framed as remote, underdeveloped, and demographically declining. Yet these same places offer vital resources to society: from biodiversity and water to cultural landscapes, food traditions, and rural livelihoods. In our recent article published in the Journal of Rural Studies, we ask how economic activity in these areas—especially in the form of value chains—can contribute not only to competitiveness but to broader territorial sustainability.

Drawing on 23 case studies from across 16 European countries, our research examined how different kinds of value chains—ranging from lamb, honey, and cheese to chestnut flour, ecotourism, and agroecological knowledge—generate and distribute value in mountain areas. Our study was part of the MOVING (MOuntain Valorisation through INterconnectedness and Green growth) Horizon 2020 project, and sought to inform policy and practice for mountain development by taking a closer look at how different forms of value (economic, socio-cultural, and environmental) emerge, shift, and circulate through production, processing, marketing, and consumption.

Beyond markets: a broader view of value

Traditional value chain analysis is rooted in business strategy and economics, focusing on how firms can improve efficiency and increase profits. In this project, we took an “extended” approach—looking not only at monetary outcomes but also at how social relationships, local knowledge, traditions, landscapes, and ecological assets are affected and valued throughout the chain.

We asked:

- How do actors perceive changes in the economic, socio-cultural, and environmental value of their activities?

- Which stages of the chain contribute most to these changes?

- And how are mountain-specific features—such as marginality, remoteness, and natural constraints—shaping these dynamics?

Methodology: grounded, comparative, transdisciplinary

Our analysis was built on detailed case study research carried out across 23 mountainous areas—from the Scottish Highlands to the Turkish Taurus Mountains, from the Carpathians to the Alps and the Iberian Peninsula. We included diverse product types (meat, cheese, wine, grain, honey, tourism, knowledge), and deliberately selected both established and emerging value chains.

Data collection combined interviews (355 in total), document analysis, and local validation workshops with over 270 stakeholders. We used a shared analytical framework to capture how value is created, transformed, and interpreted at four stages: Production, Processing, Distribution/Marketing, and Consumption. We also analysed how value chains are connected across space (e.g. tele-coupled with lowland urban markets), and how they interact with other local chains through processes of assemblage.

Key findings: patterns of value creation and retention

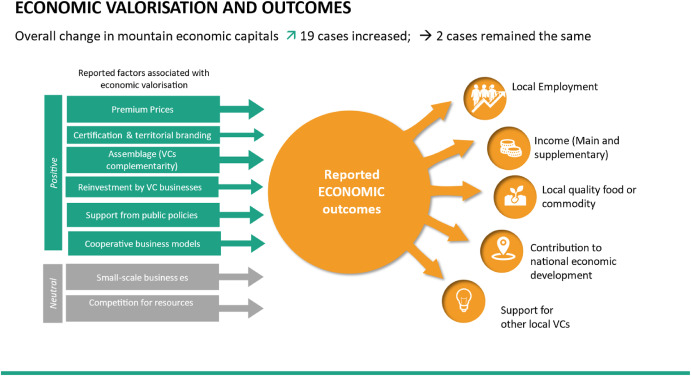

1. Economic value is often created locally, but captured elsewhere. Nearly all chains were seen to contribute positively to local economies—through jobs, income, and sometimes taxation. However, many of the economic benefits accrued outside the mountain area, especially in the later stages of the chain. Processing and marketing activities were frequently relocated to urban centres or lowland facilities, weakening the link between local production and broader territorial development.

2. Certification helps—but isn’t enough on its own. Protected Designation of Origin (PDO), organic labels, and quality marks were associated with better economic outcomes in many cases. They helped formalise connections to place and heritage, supported price premiums, and encouraged collaboration. Yet certification also introduced costs and constraints—particularly for small producers in marginal areas.

3. Socio-cultural value is significant, but often under-recognised. Many chains helped preserve traditional knowledge, reinforce community identity, and contribute to cultural landscapes. These were especially prominent in heritage-based chains (e.g. chestnut flour in Tuscany, lamb in the Alps), and those with links to tourism. However, socio-cultural benefits were less visible when ownership and control shifted away from local actors, or when value chains were fragmented.

4. Environmental value is the weakest link. Despite high dependence on natural capital, few chains were perceived to significantly improve environmental outcomes. In some cases, stakeholders expressed concerns about land pressure, pollution, or unsustainable practices. Although environmental branding was common, this did not always translate into verifiable ecological benefits—highlighting a risk of “greenwashing”.

5. Assemblages and cooperation amplify impact. Where value chains were linked—e.g. wine and tourism, meat and cheese, or flour and education—there were stronger sustainability outcomes. These “assemblages” helped diversify income, spread risk, and reinforce local identities. Cooperation (both formal and informal) was a major success factor, especially in overcoming structural disadvantages like small scale and remoteness.

6. Place-based development needs tailored support. Our findings support the principles of neo-endogenous development: combining local initiative with external support, and building on place-specific assets. But this requires tailored infrastructure, investment in skills and services, and policies that value public goods (like biodiversity, culture, and landscape) as much as private profitability.

Policy implications: valuing what matters

If the EU is serious about its Long-Term Vision for Rural Areas and Green Deal goals, mountain territories must not be left behind. Our research shows that value chains—when embedded in their territories, inclusive of local actors, and oriented toward diverse forms of value—can be powerful tools for rural resilience.

We recommend:

- Re-localising value chains, especially processing and marketing stages, to retain more value in mountain communities.

- Investing in enabling conditions, such as broadband, transport, education, and housing, to support entrepreneurship and generational renewal.

- Recognising and remunerating public goods, for instance through targeted agri-environmental schemes or territorial quality labels.

- Supporting transdisciplinary innovation, including collaborations between farmers, researchers, NGOs, and local governments.

- Strengthening mountain-specific policies, aligned with multi-level governance and sensitive to the particular needs of mountain regions.

Looking ahead

Our study shows that mountain value chains are not just about producing niche products—they are about sustaining life, landscape, and livelihoods in Europe’s highlands. By adopting a broader understanding of value and a deeper appreciation of place, policy-makers and practitioners can support these regions not as relics of the past, but as active contributors to a more just and sustainable future.

Value chains for sustainable mountain development: a qualitative understanding of 23 European cases

Value chains for sustainable mountain development: a qualitative understanding of 23 European cases

Anna Geiser, Jakub Husák, Sandra Karner, Carmen Maestre-Diaz, Raquel Moreno Vicente, Cristina Micheloni, Éva Orbán, Lucca Piccin, Mark Redman, Nehat Ramadani, Catalina Rogozan, Jean-Michel Sorba, Marco Trentin, Sofia Triliva, Murat Yercan, Tamara Zivadinovic

Journal of Rural Studies, Volume 118, 2025

This research was supported by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No. 862739 for the MOuntain Valorisation through INterconnectedness and Green growth project 2020-2024. Additional funding to support further analysis and revisions was provided by the Scottish Government’s Rural and Environment Science and Analytical Services Division through grant KJHI-C3.1 Land Use Transformations; and the Hungarian Research Council funding (NKFIH 135460).