Summary of a research paper published in Global Economic Observer – No. 2, Vol. 12 / 2024

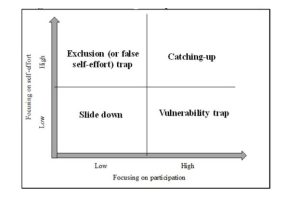

The article offers a novel theoretical framework to analyse the middle-income trap (MIT), focusing on the interplay between participation in the global economy and the strategy of self-effort. The paper introduces two distinct forms of MIT: the exclusion trap, arising from excessive reliance on self-effort without sufficient integration into the global economy, and the vulnerability trap, resulting from over-reliance on participation without developing endogenous value-creating capabilities. The article applies this framework to East-Central Europe (ECE), arguing that socialist economies previously experienced an extreme case of the exclusion trap, while the post-socialist dependent market economies are characterised by a vulnerability trap.

The middle-income trap is commonly understood as a condition in which middle-income countries struggle to make the transition to high-income status. Existing literature often attributes MIT to growth slowdowns, institutional weaknesses, and an inability to shift from resource-based to knowledge-based economies. The article critiques the traditional growth-oriented approach and proposes instead that a country’s ability to reconcile participation and self-effort is crucial for escaping the middle-income trap.

Participation refers to integration into the global division of labour through integration into global value chains (GVCs), attracting foreign direct investment (FDI) and using international trade. The benefits of participation include capital inflows, technology diffusion and market expansion. However, it also entails risks such as economic dependence, vulnerability to external shocks and the risk of remaining in a manufacturing and low value-added position in global value chains.

Self-effort, on the other hand, refers to internal value-creating capacity-building efforts, including investment in education, innovation, domestic business support and institutional development. While self-effort can promote long-term economic resilience and competitiveness, overemphasis on it without participation can lead to isolation and inefficiency.

The paper outlines how the ECE countries have experienced both manifestations of the middle-income trap. Under socialist regimes, these economies pursued a misguided strategy of self-effort, focusing on autarky and centralised planning. This approach led to inefficiency and technological stagnation, creating what the article calls an “exclusion trap”. Lack of participation in the global economy hindered access to modern technologies and competitive pressures, leading to economic underperformance. The problem was an excessive focus on inefficient self-effort without participation.

With the transition to market economies in the 1990s, the ECE countries rapidly embraced economic openness, integrating into GVCs and attracting FDI. This led to significant economic growth and structural transformation. However, the heavy reliance on foreign capital and markets led to a “vulnerability trap” in which domestic industries became dependent on foreign firms and domestic innovation capabilities remained underdeveloped.

The article presents empirical evidence to support these claims, using various economic indicators such as trade openness, FDI stocks, human capital development and innovation metrics. The data show that while ECE countries have a high level of participation in the global division of labour, their self-effort indicators, such as R&D expenditure and tertiary education attainment, lag behind those of more developed economies.

For example, the average economic openness of the ECE countries reached 139% of GDP in 2018, indicating deep integration in global trade. FDI stocks as a percentage of GDP also increased significantly, with Hungary reaching 81% in 2011. However, spending on education and R&D remained low, with the regional average education expenditure at 4.32% of GDP and R&D investment at 0.62%, significantly lower than in Western European countries.

The consequences of the vulnerability trap are evident in the dual economic structure of the ECE countries. Foreign firms dominate high-value-added activities, while domestic firms are relegated to lower-value tasks, leading to a productivity gap. In 2018, foreign firms accounted for 44% of total value added in the region, with Hungary and Slovakia showing particularly high levels of foreign dependence.

The article argues that to escape the middle-income trap, ECE countries must balance participation and self-effort. This requires targeted policies to enhance domestic value-creating capabilities while maintaining integration with the global economy. Key policy recommendations include increasing investment in education to equip the workforce with the skills needed for higher value-added industries, strengthening R&D funding, fostering collaboration between academia and industry, and encouraging domestic firms to invest in technological upgrading. In addition, the article highlights the need for state-led industrial policies to support strategic sectors, facilitate technology transfer and reduce dependence on foreign firms.

In conclusion, the paper provides a comprehensive analysis of the middle-income trap in East-Central Europe through the lens of participation and self-effort. The article’s model highlights the need for a balanced approach to economic development, emphasizing that excessive focus on either strategy can lead to stagnation. The study contributes to the broader discourse on development economics by offering a nuanced understanding of the challenges faced by middle-income countries and proposing strategies to overcome them.