Accessible, But Not Acceptable

András Deák and John Szabo

Institute of World Economics at the Centre for Economic and Regional Studies

From the very day that European leaders entertained the idea of importing Soviet natural gas in the 1960s, many criticized the decision — citing supply security and geopolitical concerns.  Dependence on oil and natural gas exports from the Soviet Union and, subsequently, Russia, continued to be regarded as geopolitically precarious and insecure. As the eminent scholar Per Högselius writes in “Red Gas”: “Soviet natural gas, to a certain extent, did function, and was perceived of as an energy weapon and … it continues [to] do so in an age when the gas is no longer red.” The negative image of Russian natural gas persisted — especially as the geopolitical situation between the West and Russia deteriorated after the “color revolutions” in the post-Soviet space in the mid-2000s — but the share of Russian imports continued to grow.

Dependence on oil and natural gas exports from the Soviet Union and, subsequently, Russia, continued to be regarded as geopolitically precarious and insecure. As the eminent scholar Per Högselius writes in “Red Gas”: “Soviet natural gas, to a certain extent, did function, and was perceived of as an energy weapon and … it continues [to] do so in an age when the gas is no longer red.” The negative image of Russian natural gas persisted — especially as the geopolitical situation between the West and Russia deteriorated after the “color revolutions” in the post-Soviet space in the mid-2000s — but the share of Russian imports continued to grow.

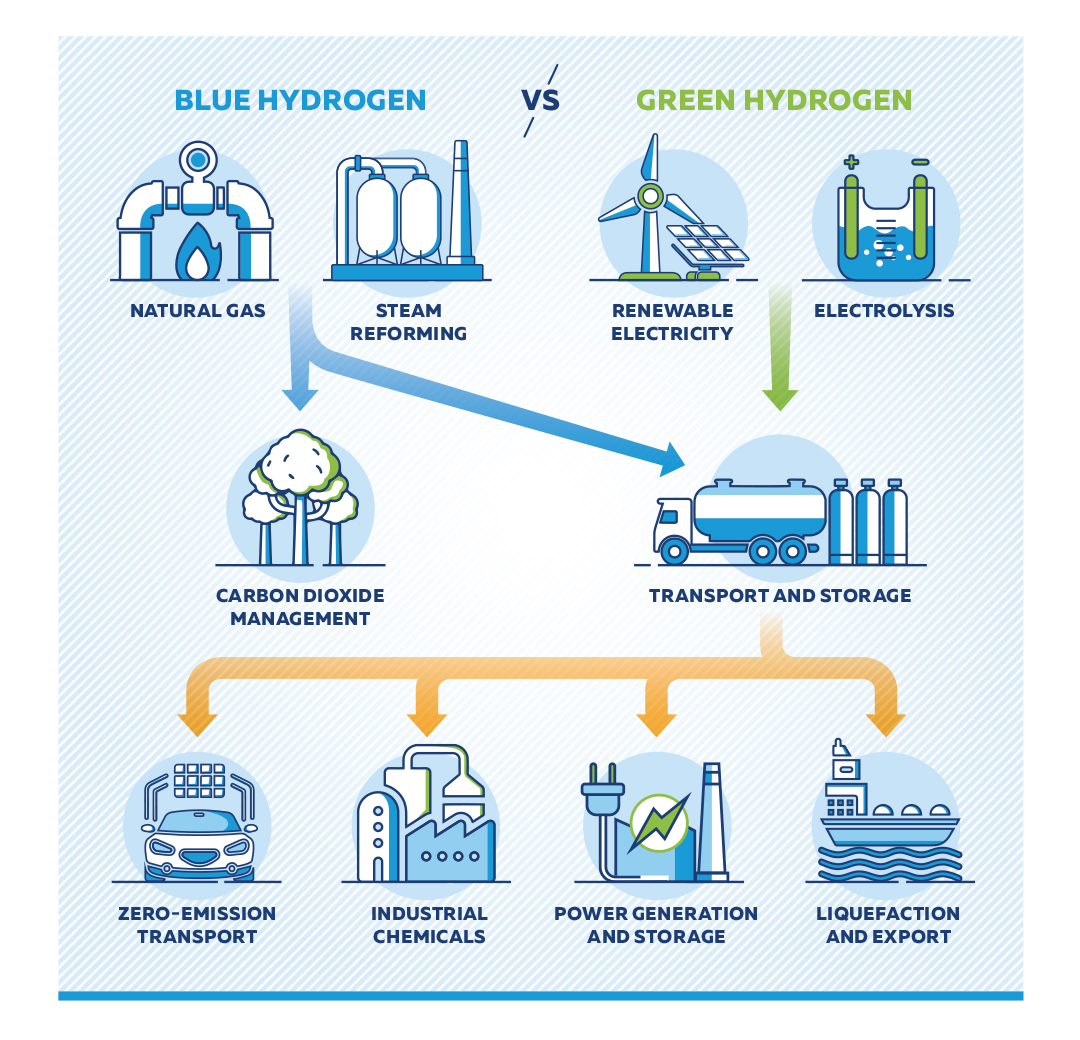

Russia’s majority state-owned energy giant Gazprom substantially decreased pipeline flows of natural gas to Europe when Russia again invaded Ukraine in February 2022. The company’s share of European Union gas imports decreased from more than 40% in 2021 to a mere 8% by 2023. Even if the Russian liquefied natural gas (LNG) imports that have increased over the past two years are included, less than 15% of EU imports originate from Russia. Only a handful of nations in Central and Eastern Europe, namely Austria, Croatia, Hungary and Slovakia, have chosen to maintain pipeline imports — decisions based on a combination of geographical and political factors. Nevertheless, European natural gas markets have undergone “de-Russification,” inviting a reassessment of the future of natural gas in Europe.